Post by petrolino on Mar 21, 2020 0:56:50 GMT

New York Nightmares

So, you had Tobe Hooper from Austin, Texas, and Wes Craven from Cleveland, Ohio, psychedelic cities with their own stories to tell. These men reshaped the American horror cinema landscape with the help of two New Yorkers; John Carpenter, who was born in Carthage (though raised in Kentucky), and George Romero of the Bronx (he later relocated to Pennsylvania).

Tobe Hooper

"I was sixteen years old the first time I saw The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. Having obtained it through dubious means (and against the will of my parents), I watched it in secret in the family computer room. After it was over, I emerged from that dark room feeling like I’d survived some kind of test - a self-inflicted crucible of horror. The scar tissue on my brain was thicker, and I could dive into even darker corners of this genre that had obsessed me for years. I didn’t know who Tobe Hooper was (beyond the director of Poltergeist) but I suspected he was some kind of next-level shock maestro - a sick mind who could conjure up unexplainable nightmares. I was genuinely intimidated by the idea of watching his other films.

Thirteen years later I watched Tobe Hooper’s debut, Eggshells (1969), for the first time, in a moment of mourning for the quietly fantastic filmmaker whose work I’d grown to love. It was a complete and total revelation. Not only did I discover a weird Rosetta Stone film that seems to reference several of Hooper’s later works, I also discovered Tobe Hooper, the psychedelic hippie and experimental filmmaker. The man who lived through an incredibly romanticized period in the history of my city, and whose debut film held the same DNA as several other Austin-based films, but was also wholly its own freak-out. Eggshells essentially performed the act of re-contextualizing all of its director’s work through a hallucinatory lens.

Eggshells (which, at the time of its making, was sub-titled “An American Freak Illumination”) was written by Hooper and Texas screenwriter Kim Henkel (who also co-wrote Chain Saw). In the tradition of many Austin-area debuts by first-time directors Eggshells eschews plot entirely - much like Richard Linklater’s It's Impossible to Learn How to Plow by Reading Books (1988), or Eagle Pennell’s The Whole Shootin' Match (1978). However, Eggshells sets itself apart from those films by laying out its rambling vision of hippie life in Austin, Texas in a series of acid-splashed reveries: A man sword-fights himself in a basement filled with smoke. A couple luxuriates in the comfort of a plastic dome. A room paints itself in a frenetic bit of experimental animation. A man drives into a field, lights his car on fire, rips off all his clothes and then frolics away as it explodes. Hooper’s camera runs wild through a psychedelic gauntlet of reality-shredding images, and it’s in those images where it becomes most apparent that Eggshells is actually a really incredible companion film to the director’s best-known horror opus.

Eggshells itself is in no way a horror film, unless you consider life amongst the hippies to be horrifying (some people do!). If anything, it’s a sunshiny flipside to the macabre lunacy of Hooper’s second directorial effort. However, the signature psychedelia of Eggshells worms its way into The Texas Chain Saw Massacre in unexpected ways. If Eggshells is “an American Freak Illumination”, then Chain Saw is “An American Freak Nightmare” - a trip gone horribly wrong. Consider some of the visions that Chain Saw employs: solar flares, extreme close-ups of darting eyeballs, chickens in cages - all bound up in a super grainy splotch of reds, oranges, and blues. These terrifying beats of pure tonal horror feel ripped straight out of someone’s acid-addled brain."

Thirteen years later I watched Tobe Hooper’s debut, Eggshells (1969), for the first time, in a moment of mourning for the quietly fantastic filmmaker whose work I’d grown to love. It was a complete and total revelation. Not only did I discover a weird Rosetta Stone film that seems to reference several of Hooper’s later works, I also discovered Tobe Hooper, the psychedelic hippie and experimental filmmaker. The man who lived through an incredibly romanticized period in the history of my city, and whose debut film held the same DNA as several other Austin-based films, but was also wholly its own freak-out. Eggshells essentially performed the act of re-contextualizing all of its director’s work through a hallucinatory lens.

Eggshells (which, at the time of its making, was sub-titled “An American Freak Illumination”) was written by Hooper and Texas screenwriter Kim Henkel (who also co-wrote Chain Saw). In the tradition of many Austin-area debuts by first-time directors Eggshells eschews plot entirely - much like Richard Linklater’s It's Impossible to Learn How to Plow by Reading Books (1988), or Eagle Pennell’s The Whole Shootin' Match (1978). However, Eggshells sets itself apart from those films by laying out its rambling vision of hippie life in Austin, Texas in a series of acid-splashed reveries: A man sword-fights himself in a basement filled with smoke. A couple luxuriates in the comfort of a plastic dome. A room paints itself in a frenetic bit of experimental animation. A man drives into a field, lights his car on fire, rips off all his clothes and then frolics away as it explodes. Hooper’s camera runs wild through a psychedelic gauntlet of reality-shredding images, and it’s in those images where it becomes most apparent that Eggshells is actually a really incredible companion film to the director’s best-known horror opus.

Eggshells itself is in no way a horror film, unless you consider life amongst the hippies to be horrifying (some people do!). If anything, it’s a sunshiny flipside to the macabre lunacy of Hooper’s second directorial effort. However, the signature psychedelia of Eggshells worms its way into The Texas Chain Saw Massacre in unexpected ways. If Eggshells is “an American Freak Illumination”, then Chain Saw is “An American Freak Nightmare” - a trip gone horribly wrong. Consider some of the visions that Chain Saw employs: solar flares, extreme close-ups of darting eyeballs, chickens in cages - all bound up in a super grainy splotch of reds, oranges, and blues. These terrifying beats of pure tonal horror feel ripped straight out of someone’s acid-addled brain."

- Zane Gordon-Bouzard, 'The Psychedelic Illumination Of Tobe Hooper’s Eggshells'

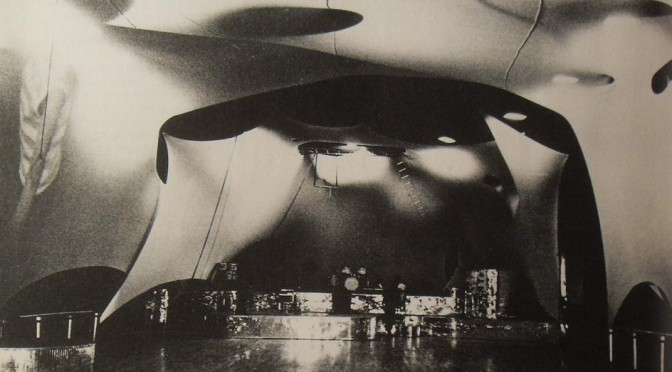

'Eaten Alive' - Wayne Bell & Tobe Hooper

-

Wes Craven

"Wes Craven studied writing and philosophy at Hopkins in the 1960s. In Wes Craven: The Man and His Nightmares, Craven describes his period in Baltimore as one of great growth:

“As a graduate student at Johns Hopkins, I did a prodigious amount of intellectual work with about a dozen other young students who were struggling with the same issues. We were the literary outcasts on one hand and the literary lions on the other.” He also noted that his time at Johns Hopkins involved “psychedelic drugs, meditation, and Eastern philosophy.”

For his Master’s thesis, Craven wrote a spooky novel that featured a graveyard, a dwarf, and a schizophrenic kid. No one would publish it–perhaps fortunately for us all. Within a few years, Craven abandoned his novel and began writing and directing the terrifying movies that have provided millions of people with millions of nightmares: The Last House on the Left; Nightmare on Elm Street; and Scream, just to name a few."

“As a graduate student at Johns Hopkins, I did a prodigious amount of intellectual work with about a dozen other young students who were struggling with the same issues. We were the literary outcasts on one hand and the literary lions on the other.” He also noted that his time at Johns Hopkins involved “psychedelic drugs, meditation, and Eastern philosophy.”

For his Master’s thesis, Craven wrote a spooky novel that featured a graveyard, a dwarf, and a schizophrenic kid. No one would publish it–perhaps fortunately for us all. Within a few years, Craven abandoned his novel and began writing and directing the terrifying movies that have provided millions of people with millions of nightmares: The Last House on the Left; Nightmare on Elm Street; and Scream, just to name a few."

- Rachel Monroe, Baltimore Fishbowl

Interview with Don Peake (composer of 'The Hills Have Eyes' / 'The People Under The Stairs') | 'Water Music' - David Hess (composer of 'The Last House On The Left')

..

-

George Romero

'The University Library System (ULS) at the University of Pittsburgh has acquired the archives of the late filmmaking pioneer George A. Romero.

The collection is composed of three separate archives belonging to his widow Suzanne Desrocher-Romero, daughter Tina Romero and business partner and friend Peter Grunwald. Beginning in 1968 with “Night of the Living Dead,” Romero revolutionized the horror genre, infusing it with intelligence, humor, social consciousness and, of course, unforgettable scares. His overall contributions will soon be accessible to allow scholars, students, filmmakers and fans worldwide to trace Romero’s projects from inception to completion.

“On behalf of the George Romero Estate and the George A. Romero Foundation, we are pleased that George’s archive is where it belongs — at the esteemed University of Pittsburgh University Library System and the great city of Pittsburgh,” Desrocher-Romero said. “We are excited to help contribute to the advancement of George’s legacy as an icon and a filmmaker.”

The collection of personal and professional materials from George Romero spans the past 50 years or more. It ranges from screenplays (both produced and unproduced) along with script notes, props, promotional materials and video (both test shots and produced footage).

Highlights of the George A. Romero Collection include:

* The original annotated script for the 1968 classic “Night of the Living Dead.”

* Romero’s unproduced adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe’s “Masque of the Red Death.” The script describes one scene: “Psychedelic images flash all around. Another CHEMICAL ORGY is in progress.”

* Photographs from the set of “Dawn of the Dead.”

* A foam latex zombie head.

“When my dad came to Pittsburgh as a student at Carnegie Mellon, he never would have imagined that one day the city would be known as ‘The Zombie Capital of the World.’ I’m so excited for people to discover some of the treasures I grew up with,” Romero said.

“George was a natural teacher,” said Grunwald. “He would have loved knowing that his collection would be used to educate and inspire future generations.”

Using the George A. Romero Collection as a foundation, Pitt’s ULS intends to establish an international scholarly resource for the research and study of horror and science fiction, which will build upon the existing strengths within Archives & Special Collections. A multimedia exhibit will be open to the public and located on Hillman Library’s third floor, which is now undergoing a modernization that is expected to be done in 2020.

The Romero Collection will be complemented by ULS’s growing treasure of full runs of major science fiction pulp titles; thousands of science fiction paperbacks from the 1960s–80s; hundreds of comic books and fanzines; programs from stage performances of horror and science fiction plays; and film scripts from Romero’s contemporaries, including John Carpenter and Wes Craven as well as authors Stephen King and Clive Barker.'

The collection is composed of three separate archives belonging to his widow Suzanne Desrocher-Romero, daughter Tina Romero and business partner and friend Peter Grunwald. Beginning in 1968 with “Night of the Living Dead,” Romero revolutionized the horror genre, infusing it with intelligence, humor, social consciousness and, of course, unforgettable scares. His overall contributions will soon be accessible to allow scholars, students, filmmakers and fans worldwide to trace Romero’s projects from inception to completion.

“On behalf of the George Romero Estate and the George A. Romero Foundation, we are pleased that George’s archive is where it belongs — at the esteemed University of Pittsburgh University Library System and the great city of Pittsburgh,” Desrocher-Romero said. “We are excited to help contribute to the advancement of George’s legacy as an icon and a filmmaker.”

The collection of personal and professional materials from George Romero spans the past 50 years or more. It ranges from screenplays (both produced and unproduced) along with script notes, props, promotional materials and video (both test shots and produced footage).

Highlights of the George A. Romero Collection include:

* The original annotated script for the 1968 classic “Night of the Living Dead.”

* Romero’s unproduced adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe’s “Masque of the Red Death.” The script describes one scene: “Psychedelic images flash all around. Another CHEMICAL ORGY is in progress.”

* Photographs from the set of “Dawn of the Dead.”

* A foam latex zombie head.

“When my dad came to Pittsburgh as a student at Carnegie Mellon, he never would have imagined that one day the city would be known as ‘The Zombie Capital of the World.’ I’m so excited for people to discover some of the treasures I grew up with,” Romero said.

“George was a natural teacher,” said Grunwald. “He would have loved knowing that his collection would be used to educate and inspire future generations.”

Using the George A. Romero Collection as a foundation, Pitt’s ULS intends to establish an international scholarly resource for the research and study of horror and science fiction, which will build upon the existing strengths within Archives & Special Collections. A multimedia exhibit will be open to the public and located on Hillman Library’s third floor, which is now undergoing a modernization that is expected to be done in 2020.

The Romero Collection will be complemented by ULS’s growing treasure of full runs of major science fiction pulp titles; thousands of science fiction paperbacks from the 1960s–80s; hundreds of comic books and fanzines; programs from stage performances of horror and science fiction plays; and film scripts from Romero’s contemporaries, including John Carpenter and Wes Craven as well as authors Stephen King and Clive Barker.'

- University Of Pittsburgh

Interview with George Romero | 'Dawn Of The Dead' - Goblin

..

-

John Carpenter

Interview Excerpt ~ John Carpenter at the A.V. Club

AVC: Before you started making films, you played in a psychedelic rock band called Kaleidoscope.

JC: When we started out we were a high school band. But then we went to college and played fraternity gigs, which were really fun to play. Those guys got so drunk! And everything sounded good to them. And we kept getting hired to do it. So we played a lot of soul music, a lot of rock ’n’ roll, and we started trying a lot of stuff that was popular at the time: “White Rabbit,” Jimi Hendrix. I wouldn’t say that we were solely psychedelic, but we had a great time doing it. It was a great way to meet girls, a great way to make a few bucks. I could have done that maybe, but I would still be there.

AVC: Did you just say to yourself, if I’m going to do this movie thing, I just need to go ahead and do it?

JC: Well, there came a time when I realized, what am I gonna do here in Bowling Green, [Kentucky]? That’s where I grew up. I could become an English teacher. I could continue to play in a rock ’n’ roll band with the dreams of making it big. But there’s no fucking way. Or I could really try this out. I somehow got accepted to USC and my dad sent me. I don’t know how I got accepted, actually; I wasn’t that smart. But you have to realize, it was cheap back then. My God, like a thousand dollars a semester. Nowadays— what? How much do they pay? It’s unbelievable. It’s wrong. Absolutely wrong.

AVC: Everyone wants to direct nowadays, but it was still something of a crazy career choice at that time, wasn’t it?

JC: Absolutely. It was nuts. No one did that. I remember the first time reading about it. It was in Time magazine and it said you could actually go to school and become a movie director. It was like, what?

AVC: If your father was disappointed you didn’t turn out to be a violin virtuoso, he must have been thrilled when you decided to go to film school.

JC: He figured he’d let me try. I don’t think he thought I had a shot. But he got real happy when I started supporting myself. Real happy. To him, that was me making it, being able to pay my own bills. I have to tell you, a lot of it’s luck, like anything else. A lot of the most talented people I went to school with never got a shot.

AVC: You have to have an obsessive quality, not just to make a movie, but to get to the point where you can make one, and another and another.

JC: Oh God, yes. [Laughs.] That’s a huge deal. You have to be unnaturally obsessed to do it. Almost crazy. A lot of people just wanted a life. They didn’t want to do this shit, put up with this.

JC: When we started out we were a high school band. But then we went to college and played fraternity gigs, which were really fun to play. Those guys got so drunk! And everything sounded good to them. And we kept getting hired to do it. So we played a lot of soul music, a lot of rock ’n’ roll, and we started trying a lot of stuff that was popular at the time: “White Rabbit,” Jimi Hendrix. I wouldn’t say that we were solely psychedelic, but we had a great time doing it. It was a great way to meet girls, a great way to make a few bucks. I could have done that maybe, but I would still be there.

AVC: Did you just say to yourself, if I’m going to do this movie thing, I just need to go ahead and do it?

JC: Well, there came a time when I realized, what am I gonna do here in Bowling Green, [Kentucky]? That’s where I grew up. I could become an English teacher. I could continue to play in a rock ’n’ roll band with the dreams of making it big. But there’s no fucking way. Or I could really try this out. I somehow got accepted to USC and my dad sent me. I don’t know how I got accepted, actually; I wasn’t that smart. But you have to realize, it was cheap back then. My God, like a thousand dollars a semester. Nowadays— what? How much do they pay? It’s unbelievable. It’s wrong. Absolutely wrong.

AVC: Everyone wants to direct nowadays, but it was still something of a crazy career choice at that time, wasn’t it?

JC: Absolutely. It was nuts. No one did that. I remember the first time reading about it. It was in Time magazine and it said you could actually go to school and become a movie director. It was like, what?

AVC: If your father was disappointed you didn’t turn out to be a violin virtuoso, he must have been thrilled when you decided to go to film school.

JC: He figured he’d let me try. I don’t think he thought I had a shot. But he got real happy when I started supporting myself. Real happy. To him, that was me making it, being able to pay my own bills. I have to tell you, a lot of it’s luck, like anything else. A lot of the most talented people I went to school with never got a shot.

AVC: You have to have an obsessive quality, not just to make a movie, but to get to the point where you can make one, and another and another.

JC: Oh God, yes. [Laughs.] That’s a huge deal. You have to be unnaturally obsessed to do it. Almost crazy. A lot of people just wanted a life. They didn’t want to do this shit, put up with this.

'Le Trente-Huit Cunegonde' - The Firesign Theater (attended by University of Southern California student John Carpenter) | 'Assault On Precinct 13' - John Carpenter

..

All of which, I hope, serves to illustrate how the cornerstones of modern American horror cinema were built upon psychedelic frenzy. But I digress ...

--

New York, New York

'The Proper Ornaments' - The Free Design

'Shadows Breaking Over My Head' - The Left Banke

'Chess Game' - Circus Maximus

'Once Upon A Dream' - The Rascals

'Velvet Cave' - Silver Apples

'Ice Cream Song' - David Hess

'I'd Rather Be Dead' - Harry Nilsson

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/L-264617-1315329639.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-4064472-1356256099-5565.jpeg.jpg)

/https://contest-public-media.si-cdn.com/669d2078-bece-4be1-8338-0aacbc12ea8f.jpg)