Post by paulslaugh on Mar 8, 2023 11:00:49 GMT

www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/mar/07/great-atlantic-sargassum-belt-seaweed-visible-from-space

Seaweed has been having a moment. Eco-influencers and columnists rave about its benefits, in everything from beauty products to biofuels. Jamie Oliver has embraced it as a recipe ingredient; Victoria Beckham uses it to keep off the pounds. And they’re right: seaweed is packed with nutrition, it sucks up carbon and is an amazingly versatile addition to the green economy.

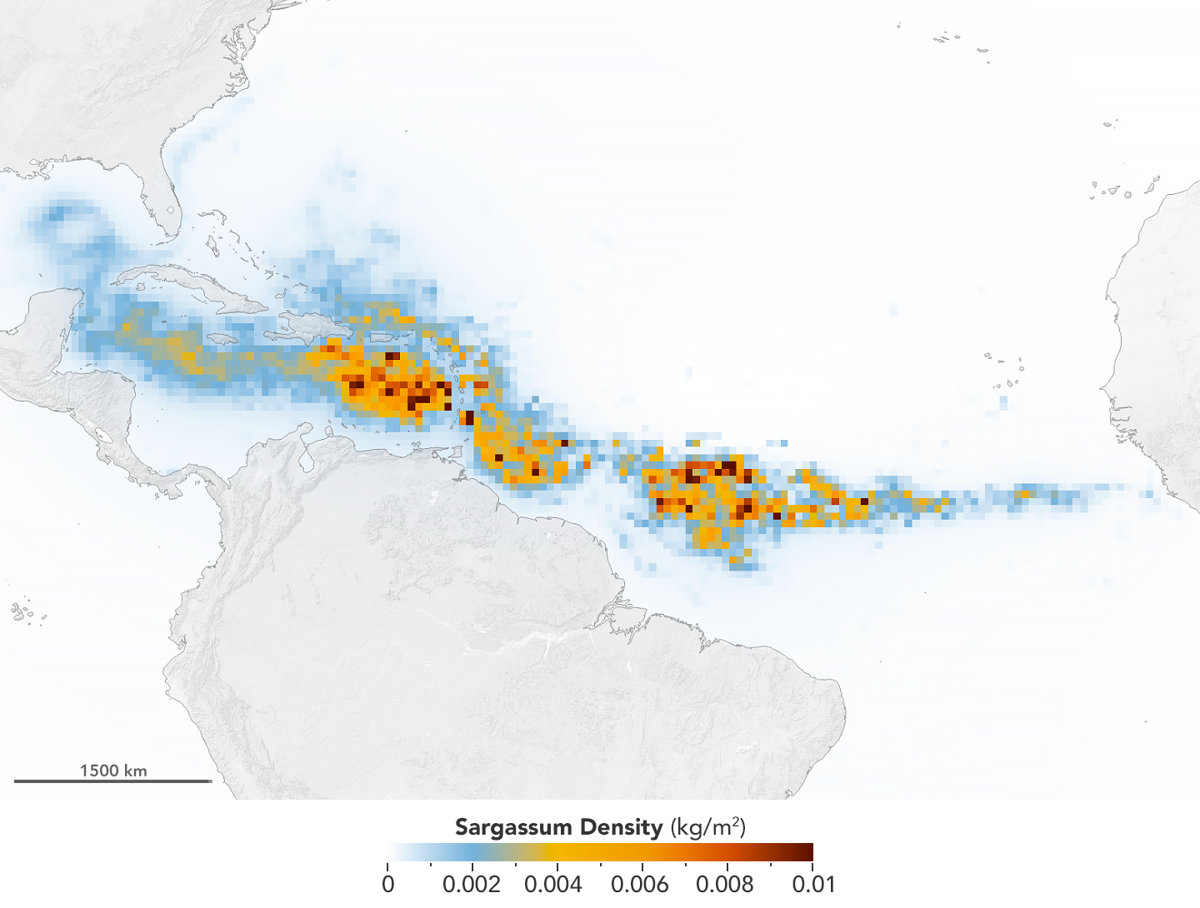

But one type of seaweed is not a benign force. Vast fields of sargassum, a brown seaweed, have bloomed in the Atlantic Ocean. Fed by human activity such as intensive soya farming in the Congo, the Amazon and the Mississippi, which dumps nitrogen and phosphorus into the ocean, the sargassum explosion is by far the biggest seaweed bloom on the planet. The Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt, as it’s known, is visible from space, stretching like a sea monster across the ocean, with its nose in the Gulf of Mexico and its tail in the mouth of the Congo.

“I think I’ve replaced my climate change anxiety with sargassum anxiety,” says Patricia Estridge, CEO of Seaweed Generation, a UK startup working to make seaweed commercially viable.

Sargassum’s appearance can be deceiving. It is beautiful, layered like golden mats on the surface of the open ocean. Distinguished by bubble-like formations in its stems that keep it floating on the surface, pelagic sargassum has sloshed about in the Atlantic since well before Christopher Columbus sailed across the wide Sargasso Sea: in 1492, he wrote that he feared his boat would be trapped in it. But even early witnesses recognised its value: it provides a safe harbour and breeding ground for fish, turtles and other marine life. Under the surface it teems with life, like an upside-down reef.

What is alarming, is the rate at which it is growing. Oceanographer Ajit Subramaniam, who has run scientific research expeditions in the South Atlantic for 25 years, first noticed it in 2018. “Here was something I’d never seen before,” he says. “One moment we were in the blue sea, then bam! It was all around the ship for tens, hundreds of metres.”

Unwilling to believe his eyes, he talked to other oceanographers, who confirmed that there was a huge sargassum bloom in the South Atlantic. Chuanmin Hu and his team from the University of South Florida’s (USF) optical oceanography laboratory had been monitoring it using satellite imagery since 2011 and had seen it explode in size. In June 2022, Hu estimated the size of the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt to be 24.2m tonnes – about four times the weight of the Great Pyramid of Giza.

A sargassum landing event is a spectacular phenomenon. Vast rafts arrive without warning, often in calm sunny weather at the height of tourist season, smothering miles of coastline in golden seaweed, which piles up, sometimes metres high, turning brown and fetid as it rots.

The first places to really feel the impact of sargassum were the Windward Islands in the Caribbean. Shelly-Ann Cox, chief fisheries officer for the Barbados government, has been working on sargassum mitigation for more than a decade. She describes the environmental and economic fallout as catastrophic: “Every year we’re seeing more and more countries reporting of the influx, and the devastating impacts on tourism, fishery sectors and transport.”

Sargassum assaults harm coastal wildlife and fish, and interfere with vital infrastructure, including water and power supplies. In addition, the hydrogen sulphide released when it decays has been shown to cause a range of human health problems, from mild headaches or eye irritation to unconsciousness and worse, while a 2022 paper has linked it to an increased risk of serious pregnancy complications in women living on the coast.

Wildlife is affected when sargassum blocks light to the seabed in shallower waters, while newly hatched turtles are unable to crawl to the sea over mountains of rotting seaweed.

Sargassum blooms fluctuate: it is most abundant in summer when the sea is calm and blue, before storms break up and scatter the golden mats. But also clear from the data, is that it is growing inexorably, fed by the climate crisis. Increased sea surface temperatures, upwelling and changing currents have combined with nutrients caused by human activity such as sewage and soya farming in the basins of the great rivers of North and South America, and Africa. Sand blown from the Sahara also brings with it iron and other essential minerals.

A more basic problem, however, is how to dispose of this contaminated biomass. Some have suggested using it as a fertiliser, but the heavy metals it contains – particularly arsenic – make it dangerous to feed to plants. Composting, too, could allow the arsenic to leach into groundwater, then drinking water and the food chain, leading several Caribbean nations to ban sargassum composting. As for industrial uses, removing the heavy metals requires so much processing that it is not cost-effective.

“There are so many climate-positive uses for seaweed, but then there are many different seaweeds in the ocean,” says Estridge. “No one could think of a commercially viable solution for sargassum.”

Jeff Davis, of the Georgia Institute of Technology, has brought together a team of undergraduates to work on this “grand challenge”. The group of young engineers and biologists travelled to the Dominican Republic to understand the scale of the problem and try to find solutions. Biology student Harshini Vummadi is exploring its uses in purifying water. Other team members have experimented with using it as a building material, or as a biofuel, using black soldier flies to “process” it, which are later removed.

Lakes Beach in St Andrew, Barbados. Sargassum is smothering Caribbean coasts from Puerto Rico to Barbados, killing wildlife, affecting the tourism industry and releasing toxic gases. Photograph: Kofi Jones/AP

“There are so many brilliant minds working on this – they just need the investment,” Cox says. But no idea has yet stood out enough to attract investment: sargassum does not, yet, seem to have the capacity to make anyone rich.

Nevertheless, Subramaniam argues that the world owes it to the Caribbean nations to help them to deal with the threat of sargassum, noting that they contribute least to the climate crisis yet are facing a direct impact. “I would like to figure out a financing model where we can actually have credit going to communities in Barbados for the carbon that is sequestered,” he says.

And sargassum’s ability to suck up carbon is behind what it probably the wildest and most ambitious plan to date: capture it using robots, bundle it up and sink it to the bottom of the sea.

“There is a lot of carbon biomass associated with sargassum – about 3m tonnes in the Great Sargassum Belt,” Subramaniam notes. “Through photosynthesis it is taking up atmospheric carbon dioxide and converting that into organic carbon.” Sinking it to the bottom of the sea would store that carbon for a couple of centuries, buying the Earth time to “flatten the carbon curve”, he says.

With the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change stating that 10bntonnes of carbon will need to be removed every year by 2050 to keep global heating below 1.5C, the Great Atlantic Sargassum belt contains a fraction of what needs to be sequestered – but it could be scaled up with seaweed cultivation.

Artist’s impression of the robot that will collect and sink the sargassum.

An artist’s impression of the robots that will collect, bundle and sink the sargassum. Photograph: Seaweed Generation

Estridge is forging ahead. At Seaweed Generation she developed technology to use the seaweed as a carbon sink. The firm has built a robot – “like a cross between Pac-Man and a Roomba” – to collect and sink the blooms, and she hopes carbon credits will provide the income to fund the operation.

Subramaniam and Estridge argue that the robots must sink the sargassum in the deep ocean, because in shallow waters it could rot and release methane. Subramaniam calculates that sinking the seaweed to a depth of between 2,000 and 4,000 metres will keep it submerged for several hundred years.

Both teams are testing their ideas: Subramaniam is seeing how the seaweed behaves in very deep water, while Seaweed Generation is working with partners in the Caribbean to follow the performance of the robot.

“The idea that it can be a nature-based solution for getting rid of some of this very small fraction – but still significant amount – of atmospheric carbon dioxide, I think is an important and exciting idea,” Subramaniam says.

Nevertheless, they fear it is only when the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt hits the affluent coasts of the Florida Keys or swamps the beaches of Cancún during spring break that significant investment will materialise. “Outside the Caribbean, no one is really talking about it,” says Harshini.

This article was amended on 7 March 2023 to remove an incorrect mention of Ecuador (misspelled as “Equador”) in reference to the South Atlantic.

But one type of seaweed is not a benign force. Vast fields of sargassum, a brown seaweed, have bloomed in the Atlantic Ocean. Fed by human activity such as intensive soya farming in the Congo, the Amazon and the Mississippi, which dumps nitrogen and phosphorus into the ocean, the sargassum explosion is by far the biggest seaweed bloom on the planet. The Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt, as it’s known, is visible from space, stretching like a sea monster across the ocean, with its nose in the Gulf of Mexico and its tail in the mouth of the Congo.

“I think I’ve replaced my climate change anxiety with sargassum anxiety,” says Patricia Estridge, CEO of Seaweed Generation, a UK startup working to make seaweed commercially viable.

Sargassum’s appearance can be deceiving. It is beautiful, layered like golden mats on the surface of the open ocean. Distinguished by bubble-like formations in its stems that keep it floating on the surface, pelagic sargassum has sloshed about in the Atlantic since well before Christopher Columbus sailed across the wide Sargasso Sea: in 1492, he wrote that he feared his boat would be trapped in it. But even early witnesses recognised its value: it provides a safe harbour and breeding ground for fish, turtles and other marine life. Under the surface it teems with life, like an upside-down reef.

What is alarming, is the rate at which it is growing. Oceanographer Ajit Subramaniam, who has run scientific research expeditions in the South Atlantic for 25 years, first noticed it in 2018. “Here was something I’d never seen before,” he says. “One moment we were in the blue sea, then bam! It was all around the ship for tens, hundreds of metres.”

Unwilling to believe his eyes, he talked to other oceanographers, who confirmed that there was a huge sargassum bloom in the South Atlantic. Chuanmin Hu and his team from the University of South Florida’s (USF) optical oceanography laboratory had been monitoring it using satellite imagery since 2011 and had seen it explode in size. In June 2022, Hu estimated the size of the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt to be 24.2m tonnes – about four times the weight of the Great Pyramid of Giza.

A sargassum landing event is a spectacular phenomenon. Vast rafts arrive without warning, often in calm sunny weather at the height of tourist season, smothering miles of coastline in golden seaweed, which piles up, sometimes metres high, turning brown and fetid as it rots.

The first places to really feel the impact of sargassum were the Windward Islands in the Caribbean. Shelly-Ann Cox, chief fisheries officer for the Barbados government, has been working on sargassum mitigation for more than a decade. She describes the environmental and economic fallout as catastrophic: “Every year we’re seeing more and more countries reporting of the influx, and the devastating impacts on tourism, fishery sectors and transport.”

Sargassum assaults harm coastal wildlife and fish, and interfere with vital infrastructure, including water and power supplies. In addition, the hydrogen sulphide released when it decays has been shown to cause a range of human health problems, from mild headaches or eye irritation to unconsciousness and worse, while a 2022 paper has linked it to an increased risk of serious pregnancy complications in women living on the coast.

Wildlife is affected when sargassum blocks light to the seabed in shallower waters, while newly hatched turtles are unable to crawl to the sea over mountains of rotting seaweed.

Sargassum blooms fluctuate: it is most abundant in summer when the sea is calm and blue, before storms break up and scatter the golden mats. But also clear from the data, is that it is growing inexorably, fed by the climate crisis. Increased sea surface temperatures, upwelling and changing currents have combined with nutrients caused by human activity such as sewage and soya farming in the basins of the great rivers of North and South America, and Africa. Sand blown from the Sahara also brings with it iron and other essential minerals.

A more basic problem, however, is how to dispose of this contaminated biomass. Some have suggested using it as a fertiliser, but the heavy metals it contains – particularly arsenic – make it dangerous to feed to plants. Composting, too, could allow the arsenic to leach into groundwater, then drinking water and the food chain, leading several Caribbean nations to ban sargassum composting. As for industrial uses, removing the heavy metals requires so much processing that it is not cost-effective.

“There are so many climate-positive uses for seaweed, but then there are many different seaweeds in the ocean,” says Estridge. “No one could think of a commercially viable solution for sargassum.”

Jeff Davis, of the Georgia Institute of Technology, has brought together a team of undergraduates to work on this “grand challenge”. The group of young engineers and biologists travelled to the Dominican Republic to understand the scale of the problem and try to find solutions. Biology student Harshini Vummadi is exploring its uses in purifying water. Other team members have experimented with using it as a building material, or as a biofuel, using black soldier flies to “process” it, which are later removed.

Lakes Beach in St Andrew, Barbados. Sargassum is smothering Caribbean coasts from Puerto Rico to Barbados, killing wildlife, affecting the tourism industry and releasing toxic gases. Photograph: Kofi Jones/AP

“There are so many brilliant minds working on this – they just need the investment,” Cox says. But no idea has yet stood out enough to attract investment: sargassum does not, yet, seem to have the capacity to make anyone rich.

Nevertheless, Subramaniam argues that the world owes it to the Caribbean nations to help them to deal with the threat of sargassum, noting that they contribute least to the climate crisis yet are facing a direct impact. “I would like to figure out a financing model where we can actually have credit going to communities in Barbados for the carbon that is sequestered,” he says.

And sargassum’s ability to suck up carbon is behind what it probably the wildest and most ambitious plan to date: capture it using robots, bundle it up and sink it to the bottom of the sea.

“There is a lot of carbon biomass associated with sargassum – about 3m tonnes in the Great Sargassum Belt,” Subramaniam notes. “Through photosynthesis it is taking up atmospheric carbon dioxide and converting that into organic carbon.” Sinking it to the bottom of the sea would store that carbon for a couple of centuries, buying the Earth time to “flatten the carbon curve”, he says.

With the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change stating that 10bntonnes of carbon will need to be removed every year by 2050 to keep global heating below 1.5C, the Great Atlantic Sargassum belt contains a fraction of what needs to be sequestered – but it could be scaled up with seaweed cultivation.

Artist’s impression of the robot that will collect and sink the sargassum.

An artist’s impression of the robots that will collect, bundle and sink the sargassum. Photograph: Seaweed Generation

Estridge is forging ahead. At Seaweed Generation she developed technology to use the seaweed as a carbon sink. The firm has built a robot – “like a cross between Pac-Man and a Roomba” – to collect and sink the blooms, and she hopes carbon credits will provide the income to fund the operation.

Subramaniam and Estridge argue that the robots must sink the sargassum in the deep ocean, because in shallow waters it could rot and release methane. Subramaniam calculates that sinking the seaweed to a depth of between 2,000 and 4,000 metres will keep it submerged for several hundred years.

Both teams are testing their ideas: Subramaniam is seeing how the seaweed behaves in very deep water, while Seaweed Generation is working with partners in the Caribbean to follow the performance of the robot.

“The idea that it can be a nature-based solution for getting rid of some of this very small fraction – but still significant amount – of atmospheric carbon dioxide, I think is an important and exciting idea,” Subramaniam says.

Nevertheless, they fear it is only when the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt hits the affluent coasts of the Florida Keys or swamps the beaches of Cancún during spring break that significant investment will materialise. “Outside the Caribbean, no one is really talking about it,” says Harshini.

This article was amended on 7 March 2023 to remove an incorrect mention of Ecuador (misspelled as “Equador”) in reference to the South Atlantic.